Tree of Life

Americans are refusing vaccines because they've forgotten that children dying of infectious disease is natural.

“All the trees here, and in every forest that is not too damaged, are connected to each other through underground fungal networks. Trees share water and nutrients through the networks, and also use them to communicate. They send distress signals about drought and disease, for example, or insect attacks, and other trees alter their behavior when they receive these messages.” - Peter Wohlleben

“Scientists call these mycorrhizal networks…For young saplings in a deeply shaded part of the forest, the network is literally a lifeline. Lacking the sunlight to photosynthesize, they survive because big trees, including their parents, pump sugar into their roots through the network”

“…two massive beech trees [grow] next to each other. He points up at their skeletal winter crowns, which appear careful not to encroach into each other’s space. “These two are old friends,” he says. “They are very considerate in sharing the sunlight, and their root systems are closely connected. In cases like this, when one dies, the other usually dies soon afterward, because they are dependent on each other.” - Richard Grant, Smithsonian Magazine

There are trees everywhere.

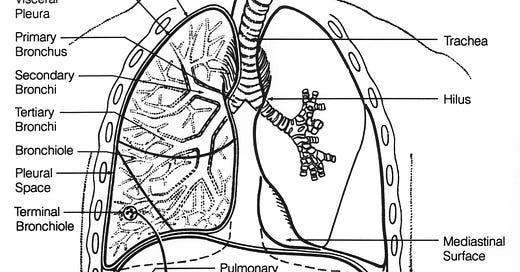

You have one in your body, it’s called the tracheobronchial tree. This tree is upside down. Or maybe you are and the tree is right-side up. The trunk of the tree is your windpipe, the trachea. The trachea begins to form when an embryo enters its second month. First there was the seed and then there was the sprout. Your trunk of a trachea has rings. It’s made up of about twenty rings held by ligaments and muscle. The trachea extends down to your lungs where it branches into the left and right bronchi. Did you know your left lung is a little smaller than your right lung? It’s leaving room for your heart. Those bronchi are respiratory passages that get smaller as they branch out into your lungs. At the end of each reaching branch is a little air sack called an alveolus. There are 600 million alveioli in your body. Alveioli work like leaves, they facilitate an exchange of gasses. They put oxygen into your blood and pull carbon dioxide out of it. Sometimes I imagine them fluttering in me when there is a breeze.

This is the tree that Covid-19 withers. Covid is caused by the virus, Sars-Cov-2. Sars-Cov-2 enters your body when you breathe and causes Covid-19, a disease that can stop your breath. If the virus is not stopped by your immune system, it travels to the surface of the cells on your alveoli. The virus pierces those cells with a spike protein and enters. (A spike protein is kind of like a key or a crowbar. It’s the thing that helps this virus get into your cells.) Infection follows. The infection thickens, inflames and fills. The hollow branches of your lungs thicken until air cannot pass through them. The alveoli, your lovely leaves, fill with fluid until there is no room for oxygen. On chest CTs, the lungs of people infected with Covid-19 look like ground glass. For people who live, lung scarring can be permanent, the branches never losing their constricting thickness. But for 621,051 people in the United States once their tree turned to glass it didn’t just wither, it shattered.

I have three children. They are growing in a viral landscape.

I have three children. They have not been infected by the disease sweeping through our forest. But their roots plunge into our shared soil. They are growing in a viral landscape. My oldest daughter entered puberty during the pandemic. She left her childhood, in form and function, somewhere between the masks and Zoom funerals. I wish she could have left it somewhere else. Sometimes I look for it, to see if we can place it somewhere safer, but it’s lost now. If recent projections are correct, she will leave puberty during the pandemic too.

While ICUs filled, emptied and filled again, my middle daughter learned to ride a bike. She stopped asking to sleep with us every night and started asking for “proof of what happens to people after they die”. The youngest? She’s spent half her life in a Covid infected world. Despite concerns over how very young children are developing during the pandemic, but she’s met all her milestones.There are a few odd gaps in her knowledge. Last May, she went into a store for the first time since the pandemic started. It was all so new to her. She screamed with delight at the carts, the aisles of toys, the stacks of chips. “IT’S WONDEWRFUL MAMA!” And it for a moment, I was able to see it was.

My oldest child has been vaccinated. My two youngest are still not eligible for the vaccine. While children have been infected with Covid-19 since the beginning of the pandemic, generally kids have been safe. I’ve never really been comforted by generalities when considering my particular children. After all, if something is generally true, that means that it isn’t always true. Children were disabled by Covid-19 during the first 18 months of the pandemic. Children died. But until the vaccines came out, I let statistics soothe my anxiety. Nearly every child would be okay. When vaccines became widely available and large swathes of eligible people refused them, I pulled those statistics close and rubbed my fingers along them like satin on a blanket. Now the Delta variant is here. The statistics aren’t enough, maybe they never were.

The statistics aren’t enough, maybe they never were.

Delta is highly transmissible. It infects more people, more quickly than the ancestral strain of Sars-Cov-2. (Yes, Sars-Cov-2 is a matriarch with many generations.) As viruses evolve, so does the truth about them. For now, Delta doesn’t appear to better at infecting children. But its increased transmission means more children will be exposed to it. As Sallie Permer, Chair of Pediatrics at New York-Presbyterian Komansky Children’s Hospital said in The Atlantic, “The more transmission you have, the more cases you have, and the more you’re going to have bad outcomes.” It’s a numbers game that will still the hands of children who still use their fingers to count to ten.

Hospital admissions prove the math. The August 4 - August 10 daily average of pediatric Covid-19 admissions increased 27% from the previous seven days. It has surpassed the peak of pediatric admissions last January. The number of children experiencing severe disease has increased too. Mild cases of Covid have risks too. Up to 10% of children who get the disease will develop long Covid. Long Covid is a months-long condition characterized by memory loss, exhaustion and shortness of breath.

It’s a numbers game that will still the hands of children who still use their fingers to count to ten.

Delta is spreading across the U.S. as pediatric hospitals deal with an enormous, out-of-season surge of RSV cases. These diseases aren’t just crowding children into hospitals, they’re themselves crowding into children. One Texas hospital has admitted 25 children suffering from both RSV and Covid. As pediatric ICUs reach capacity because of RSV and Covid, the systems capacity to care for other sick children is strained. Children suffering from other health emergencies like cancer and accidents are left without hospital beds and adequate care close to home. One Texas official said that even with life flights to other hospitals, children needing ICU care will have to wait for another child to die to get a bed.

As viruses evolve the truth about them does too. But for now what we know about Delta, and Covid-19, is that children are not specifically targeted by the virus. Kids still generally (there’s that word again) fare much better than adults when faced with the virus. Educational settings aren’t what infect kids, the community is what infects kids. Transmission at schools is the same as the transmission in the surrounding community. Sometimes it’s lower. Sitting in a classroom with other children isn’t what endangers a child. A community’s low vaccination rates is what endangers a child in the community. Communities include classrooms.

Keeping children from sitting in classrooms has caused incredible harm. During the pandemic, over a million children who should have enrolled in school, did not. Many of them were very young children from low-income neighborhoods. In this and so many other ways, the pandemic has “hardened inequities in education, setting back some of the most vulnerable students". Depression and anxiety in children doubled during the pandemic, with girls and adolescents the most affected. The suicide attempt rate among teen girls has grown by half since the pandemic started. This makes some dark sense. “Disturbances in our social rhythms significantly increase the risk – even predict – the development of major depressive episodes," according to Dr. Timothy Sullivan, chair of psychiatry and behavioral sciences at Staten Island University Hospital. Communities with high vaccination reduce transmission and protect children who cannot be vaccinated. They are able to return to classrooms and knowable social rhythms safely. Basically, if we are a forest then vaccines are how we pump sugar into our failing sapling’s roots.

The vaccines are timely because so much time had already been put into them before we needed them. The technology behind mRNA vaccines was decades in development before the first cases of Sars-Cov-2 emerged. Once the severity of the virus was known, vaccine development did not follow a single long line of linear steps. It became a thing that branched. This doesn’t mean steps were skipped, it just means they unfurled at the same time across multiple limbs. Like leaves sprouting in the spring. Trials were held in parallel, regulators across agencies worked together, manufacturing platforms proved themselves while studies were ongoing. Vaccine development took loads of money and cooperation, but no shortcuts. And the vaccines it resulted in are, frankly, pretty forking amazing.

The mRNA vaccine is not an invasion, it’s an education.

Unlike previous vaccine breakthroughs, like the polio vaccine, there is no inactive virus in the Covid vaccines. The mRNA vaccine is not an invasion, it’s an education. This makes biological sense because our bodies were built to learn. Dendritic cells are some of our bodies most eager students. They are the cells that initiate our body’s immune response to new pathogens. Their job is to recognize things that shouldn’t be in your body and then go on to help your other immune cells recognize them too. The vaccine shows your dendritic cells what the Sars-Cov-2 spike protein looks like. That’s it. It just shows them the shape of the protein.

Like good teachers assistants, the dendritic cells then show that new shape to your other immune cells. Those cells react by producing antibodies. This immune response can make you feel crummy for a day or two, but it’s worth it. After your immune cells have done their homework, they are ready to recognize and react to the real Sars-Cov-2 virus. Do you want to know something lovely? Dendrite means “branching”. Scientists named them “dendritic” cells because they have a tree like shape. They’re little trees of life. There are trees everywhere.

Vaccines aren’t perfect because they are real.

At their best, the vaccines completely decouple Sars-Cov-2 and the disease, Covid-19. Even when they are not at their best, they overwhelmingly protect against severe Covid and death. But vaccines aren’t perfect because they are real. Breakthrough infections will occur and some of them will lead to hospitalization. But even against a strain like Delta, if enough people are vaccinated, the vaccines we have are still good enough. Letting a vaccine educate your body and protect you, will also protect the children around you. Most of us want to protect children. But in a country with so many vaccines we are throwing some away, there are millions of eligible people still unvaccinated. They’ve chosen not to get the shots.When asked about the risk this creates for children who cannot be vaccinated, the standard reply is that not very many children die of Covid-19.

I can’t help thinking of the forest. The forest doesn’t wait until a critical mass of saplings are at risk to use their shared network to protect them. When the connection between trees is not too damaged, the older trees help the one, the two, the few. As healthy adults refuse the vaccine and put children at risk I can’t help asking, is our community too damaged? Is every fine filament that could connect us severed?

Is our community too damaged? Is every fine filament that could connect us severed?

Many things hurt our connections to one another. We’re an individualistic society that has never been good at caring for the individual. The American medical community has corrupted itself with eugenics, racism and misogyny. Too often when vulnerable populations have been asked to “trust the science”, they’ve been harmed. Missteps by the CDC, like discouraging masking and fumbled messaging, have decreased American trust in the agency’s recommendations. But there is more at work here than our usual cultural and institutional failings.

Misinformation and conspiracy theories passed along in Instagram stories have made people who get a yearly flu shot hostile to the Covid-19 vaccine. When the leaders of my church recently called for everyone to be vaccinated, the comment section was full of people accusing the church of getting involved in politics.

Where I see a public health tool, they see a tool of political oppression. Pathogens preceded politics and pandemics are not contained by party. It is difficult to imagine parents refusing the polio vaccine because of politics. Instead, they clamored for it, signing 600,000 children up for the trials. Still, I suppose the people who call the Covid vaccine political are making their claim true. We are entering a bigger fourth wave of the pandemic because their politics kept them from getting the vaccine. And we are entering it with every child under 12 still unvaccinated.

We’ve forgotten that the natural state of world is one where a child’s cough can metastasize into lifelong sorrow

All of this sits atop a certain kind of forgetfulness endemic in well-off, individualistic societies. We’ve forgotten that the natural state of world is one where a child’s cough can metastasize into lifelong sorrow. We don’t know how to live, or die, with a deadly infectious disease. It doesn’t seem to matter that many of us have grandparents or parents who knew people paralyzed or killed by viruses before vaccines. We have not grown up with a handful of tombstones as the only proof of siblings killed by diphtheria. We do not know the chill of hearing a family three doors down has smallpox. We’ve never had to wonder if our home is next. Our collective memory is shorter than the memory of our cells. We are shocked now when a child dies. It’s just not natural. But, of course, a child dying of an infectious disease is the most natural thing in the world. The history of humanity is one where children die.

The history of humanity is one where children die.

History is a word that could be large but that most of us keep small. Many of us only know about the history of the hundred or so years that came before us. And very few of us think about the time before history, pre-history. History requires records and for most of humanity we have not been a record keeping people. Writing systems didn’t emerge until 5,000 years ago. Homo Sapiens have been breathing, birthing and dying for 300,000 years. That seems like a long time ago. But there’s no need to think of those years as such a great separation. We’ve been taught to think of years as segments on a line, each one adding a length that distances. But Time isn’t a timeline. Time is, instead, a thing that branches. There are trees everywhere.

Time isn’t a timeline. Time is, instead, a thing that branches.

If I swung from my branch of time to one coursing 17,000 years ago through Paleolithic Europe, I’d hardly recognize the landscape. Faced with tundra and steppe, I wouldn’t know what to do. But if a little girl from 17,ooo years ago was suddenly perched on the corner of my modern street, crying and confused? I’d understand what she was immediately; a child in need of protection. I would know what to do. Walk over, kneel down next to her and ask if she needed help finding her way home. If different epochs can’t keep up us from understanding children need protection, certainly different political parties needn’t stand in our way. Of course, in this time climbing scenario, her answer would be unintelligible to me. And I’d have no idea how to get her back onto her Paleolithic branch. I guess we'd just have to sit together on that corner until we figured something out.

But if I did find a way to help her home, she’d return to a glacial age. A place where megafauna moved across the plains quickly and ice moved back and forth across the earth slowly. The Paleolithic period is just one little part of what we were taught to call the Stone Age. We call it the Stone Age because humanity’s dominant technology during that time was chipped and carved stone. The Bronze Age followed when humans learned to pull metal from rock. (Naming a whole epoch after one kind of technology is typically reductive of us, isn’t it?)

Part of a roaming hunter-gatherer society, she would have lived with a very small group of people. Once in awhile, other small groups would have joined her own for protection, for a feast, for a rite, for a time. Sometimes this gathering took place at a cave. Archaeologist Mary Conkey calls the caves where pre-historic people gathered, Places of Many Generations. They were visited over and over again for thousands of years, refugia for collective memory making and memory keeping. Sometimes I wonder if we've lost our collective memory because we've not found a place to keep it.

Archaeologist Mary Conkey calls the caves where pre-historic people gathered, Places of Many Generations.

Paleolithic people would have mostly stayed in the mouth of the cave where sunlight and starlight provided enough light. But sometimes the group pushed themselves into the solid darkness of the cave’s interior. Holding hollowed out rocks filled with animal fat and threaded with juniper twigs. Enough fuel and wick for about 30 minutes of jumping light. They carried pigment as well as fire. And then, by flickering flame they painted on the cave walls. Lions, panthers, ladders, a Venus.

Some people say they were painting a calendar of creation. Our Paleolithic girl is little and maybe not ready to paint a whole animal. But she is created and creates too. So she opens her hand and rubs ocher across it. She stretches her little fingers to make sure the pigment gets into the distal and proximal creases. And then, fingers still extended, she presses her hand into the cave wall, pushing from her toes and through her arm to make her mark clear.

We’ve created different epochs for rocks and humans, another place where time branches. In our story, both the girl and the cave intersect 17,000 years ago. A geologist would say the cave was in the Pleistocene while an anthropologist would say the girl was in the Paleolithic. As our girl presses her hand to the rock, the planes of two epochs meet. Can she feel it? When she pulls her hand back, her handprint remains.

The light moves back and forth and her fingermarks branch up and out across the cave wall. She gasps at the movement. The oxygen she pulls in from the cave travels down her trachea, into her bronchial branches through her alveoli and into her blood. There’s a quick exchange, the oxygen from inside the cave for for the carbon dioxide inside of her. She can’t know it, but the passage she’s standing in is one of many. The cave branches like her lungs. Caves breathe too. Even in a deforested ice age, there were trees everywhere.

Her handprint would remain vibrant for thousands of years, but it’s likely our girl would die in her youth. There were so many old and new dangers, old and new diseases. The bacteria that causes whooping cough was already ancient by the time our girl pressed her hand into that wall. Bordetella pertussis prefers to infect humans, there are no known animal vectors. It’s airborne and highly contagious. When everyone gathered at the cave maybe someone brought it with them, nestled inside of their nose. They sneezed and she breathed.

Her immune cells didn’t recognize it, they couldn’t protect her. A slight fever settled and broke before long nights of lumbering breath. She coughs until she breaks a rib. Her mother keeps busy, moving back and forth with water and medicinal flowers. The girl's fever returns when the pneumonia sets in. Her lungs fill with fluid and pus. She drowns while her mother holds her. There is still pigment in the creases of her fingers when her hands grow cold.

Grief and hope evolved long before our girl's birth and death.

She would have been buried with care. Her grave dug with an antler pick. Archaeologists have found evidence of flowers sprinkled on top of Paleolithic graves. Grief and hope evolved long before our girl's birth and death.

Of course, death by infectious disease didn’t just happen upon those who roamed before the ice melted. Most infectious diseases emerged as people domesticated animals and settled near one another. New diseases became old, old diseases became ancient. They infected children on different branches of time. Children died of infectious diseases in the mouths of caves, in Roman Domus, Minoan palace, Celtic roundhouse, Nubian specs, Adobe house, Victorian tenement and in stilt houses over still water. As they died, their mothers moved to and from them, trying to clear a passage for their survival. Here is some water. Here is a brew the midwife left by the front door. Here are some leeches, let them suck out the bad blood and leave the good. Here is a prayer. Here is a curse. Here is your favorite soup, fruit, honeyed candy. Just wake up darling and I’ll let you eat it all.

One family buried 13 children within a few months.

Smallpox infected pharaohs and 20th century children, its leaking pustules and 30% fatality rate connecting humans across millennia. In the 5th century BCE, Hippocrates described Diphtheria. Diphtheria is a disease that coats the back of a child’s throat with so many dead cells they suffocate to death. It was called “The Strangling Angel of Children”. Highly contagious, one 1700s outbreak in New England killed every child in the family in at least 23 households. One family buried 13 children within a few months. Their bones are still rooted in our shared ground. An Egyptian stele from 1400 BCE shows a priest with a withered, shortened leg - a common bequest of the polio virus. The priest was called “doorkeeper Roma”. The virus was already old by the time his disease altered image was carved into limestone. But age didn’t slow polio down. In the 1940s and 50s, over half a million people a year were paralyzed or killed by the virus that took doorkeeper Roma’s stride.

With vaccines, we’ve learned to pull prevention from pathogen.

A concerted worldwide vaccine campaign eradicated smallpox in the 1970s. Both polio and diphtheria can now be prevented with effective vaccines. As can so many of the other infectious diseases that left little beds empty. Public health is always a matter of access. Many children live in places where they cannot get vaccines. But if a child is born into a wealthy nation with even a semi-functional healthcare system, a simple regimen of childhood shots can help them reach adulthood. In the United States, it’s become increasingly uncommon for young hands to be stilled by ancient illnesses. When we learned to pull metal from rocks, we entered the Bronze Age. With vaccines, we’ve learned to pull prevention from pathogen. It wasn't so outlandish to think we were entering a new age. But, of course, ages aren’t points in a progressive line, they are branches budded from the same trunk. The Age of Infectious Diseases doesn’t end, it forks. We will always need new vaccines and people willing to take them.

The ventilator next to their child’s bed is a squat Tree of Life.

As the Delta variant fills pediatric ICUs beyond capacity, parents of patients learn there are trees everywhere. Even in an Intensive Care Unit. The ventilator next to their child’s bed is a squat Tree of Life. Its tubes branch out into their child's mouth and down her trachea. The machine fills her lungs with oxygen and pulls the carbon dioxide from her blood. It is flanked by intravenous poles, IV bags of antibiotics and pain medicine hang like fruit from their metallic boughs. It’s a hearty little stand of trees in a barren landscape. Everything else is white walls and black cords. Machines beep and carts in the hallways clack. The constant noise and bright light of an ICU room feels ominous, but the thing to fear is silence.

My dad died in an ICU. He was dying of acute myeloid leukemia but was killed by pneumonia. His room only became quiet once its trees could no longer sustain him. The nurses pulled the tube from his throat, they disconnected the lines from his port. Pushed the poles aside, they were just snag trees now and could bear no fruit. One nurse turned off the machines. Another pulled the blankets up over his chest. My family rushed into the room to say goodbye as the nurses left, a quick exchange of hope for grief. They’d arranged his arms on top of the blankets, maybe so we had something to hold onto while he died. There were so many of us and he only had two arms, two hands. I moved to the end of the bed and pulled his foot out from where it had been carefully tucked into blankets. I held onto his ankle while he left, a child asking her dad not to go.

A child is so small; there’s hardly enough of her for everyone who loves her to hold.

Saying goodbye to an adult is different from saying goodbye to a child in so many very big and very small ways. I can’t stop fixating on one of the very small differences. My dad was a broad man. There was almost enough of him for all of us to cling while he left. A child is so small; there’s hardly enough of her for everyone who loves her to hold. I’d be so worried about untucking the blankets around her feet. What if she felt cold?

I believe there are branching passageways beyond the mouth of death. They lead to a Place of Many Generations where the light doesn’t flicker or fade. I know we cannot keep some children from walking into those passages before us. We will always lose children to cancer, accidents, violence and even infectious diseases. But nearly every child’s death from Covid can be prevented if the community around them is vaccinated. People say if more children were disabled by Covid, if more children were dying, then they’d consider vaccination. But for hundreds of children, for a handful of children, for one child? They are unwilling.

When we lose one child, we lose an epoch.

Can we not see the tree for the forest? Our collective past and future branches through each individual child. Every lost child is one less hand pressing its mark against the bedrock of our humanity. When we lose one child, we lose an epoch.

There are trees everywhere.

You, with your branching limbs, are a tree. A dendritic cell in the body of humanity. When you get vaccinated, your strengthened immunity branches over our children and secures their roots until they can be vaccinated too. You become a Tree of Life in a sacred grove.

Covid-19 vaccines are safe, free and, in the United States, available. Find a place to get vaccinated here.

If you have questions about the Covid-19 vaccine, call your primary care physician.