By Design

White communists, socialists, feminists, and capitalists tried to engineer society using kitchen design.

12 minutes of childcare costs $5. If you enjoy my work, consider becoming a paid subscriber. When you sign up for a paid subscription, you’re giving me 12 minutes a month to write. I promise not to waste a second. (Plus there’s lots of fun member-only perks!)

Have you seen the New York Times article about rich people’s kitchens?

It’s pretty wild.

Apparently, rich people are having a couture cooling moment. The new status symbol is an invisible fridge. The invisibility is an illusion. They buy enormous sub-zero fridges for $15,000 and then stick panels on them that match their custom cabinetry. So what once looked like a fridge now looks like a cabinet. Rich people like to have two cabinet-camouflaged fridges.They usually stand next to one another, but it’s probably fine to spread them out.

There are cooling drawers too. The drawers are mostly built into kitchen islands. Although it’s increasingly common for the ultra-rich to have them installed in bathrooms for temperature controlled face creams. “Most people put four — or possibly six” cooling cubbies in the kitchen. What are all these drawers filled with? Mostly drinks. Like...so many drinks. That’s mostly what fills the second fridge too. The rich enjoy a cooled bottled beverage. The article doesn’t dig into whether the chilled bathroom drawers hold drinks too. But I bet there’s some bottled water in there. Filtered through the crystal caves of an untouched island before being bottled in artisanal plastic, or whatever.

Wealthy people want their food to be cool, but not cold. There are increasingly few freezers in the homes of the rich. Sometimes there’s a tiny one for ice cream. Apparently, freezing food is just not really done anymore. Interior designer Martin Lawrence Bullard says, “Freezing food is becoming less and less fashionable. People want to eat more organically.” Organically is doing a lot of work here. One can purchase organic meat and freeze it. That’s how my family gets its beef each year. We buy half a cow from a local rancher. A butcher divides it into steaks, roasts, ground beef, oxtails, ribs, stew bones. We keep it in our freezer. It’s an affordable way to make our meat consumption more ethical. I know vegetarians who preserve seasonal finds at the farmer’s market the same way.

Freezing is a method of food preservation that protects flavor and nutrients. It’s not really a fashion statement. I guess it’s not organic if you’re using the word to mean “natural outgrowth” because, yeah, freezing food keeps it from naturally rotting. Like, yes. Freezing does stop the organic process of decay. The rich are pro-decay. A stance one can only take today if they are very, very sure they can afford non-decaying food tomorrow.

The rich are pro-decay.

I doubt the very wealthy are asking for tiny freezers and hidden refrigerators because they are on the side of Big Bottled Beverage and Big Rot. Probably they just think it looks nice. Designers like Shannon Wolcack agree. She owns a design firm in West Hollywood where she works with clients like Hillary Duff. Why does the kitchen need to host its own persistent optical illusion? Wolcack says, “Kitchens used to be concealed. It had a door. That was where you had all your appliances. It was like the work space. And now, kitchens are more of a lifestyle. You want to make it pretty and seamless.”

And I guess this is where my brain finally exploded. Heaven forbid the kitchen feel like a work space. The work of the home isn’t really work, didn’t you know? It’s a lifestyle! It’s pretty and seamless!

Is there anything inherently wrong with sticking a panel on your fridge so that it looks like a cabinet? No, of course not. I can’t afford the style of fridge I really like. It makes some aesthetic sense to cover up the less than beautiful fridge I can afford. But the history of kitchen cabinets and the appliances tucked in snugly between them is not pretty or seamless. It’s brimming with attempted liberation, deliberate oppression, Cold War marketing and feminist utopias founded on white supremacy. And it's still stewing.

Architecture is older than our recorded history. But a practical theory of kitchen design didn't emerge until the 20th century. Until then, kitchens were just random bits of furniture and a stove shoved in attics, basements and poorly ventilated back rooms. Architects didn’t care about kitchens because they were filled with servants and lower class women and servant women. And what design did a servant or woman deserve?

After the horrors of World War I, some people decided to try to design a new world. And they were like, What the heck, let’s include kitchens. In Germany, New Frankfurt was one of those world building projects. The architects behind New Frankfurt were tasked with finding a way to build affordable housing that fostered community and equality by design. Grete Schuette-Lihotzky, the first female architect in Austria, was in charge of the kitchens.

In an interview before her death she said, “before I conceived the Frankfurt Kitchen in 1926, I never cooked myself. At home in Vienna my mother cooked, in Frankfurt I went to the Wirthaus. I designed the kitchen as an architect, not as a housewife." She was not a housewife but that did not keep her from respecting the women who were. Lihotzky took the work of the home seriously. She thought it should be treated with professional dignity.

She knew that not all women wanted to work in the home. She was, after all, one of those women. But Lihotzky was practical. She felt sure that whether they worked in the home or outside of it, women would continue to do most housework. Because of this she said, “women’s struggle for economic independence and personal development meant that the rationalization of housework was an absolute necessity.” Efficient design would help women to independence.

Using the research of home economist Christine Frederick, Lihotzky created an orderly layout of storage, appliance and work surface. Frederick was an odd silent collaborator. Lihotzky was a passionate communist dedicated to an egalitarian future. Frederick is widely credited with disseminating the 20th century version of the separate spheres of men and women. She was also influential in arguing that all mass produced home goods should be made to fall apart so that industries could keep making mass produced home goods. (This is called planned obsolescence and tech companies still do it today.) Still, Communist Lihotzky took Consumer Capitalist Frederick’s measurements seriously. Cabinets, shelves, appliances, work surfaces were each fixed in place, fitting precisely.

Inspired by the efficiency of research labs, Lihotzky standardized kitchen workflow and under cabinet storage. Your kitchen looks a little like a lab, standing work surfaces and cabinets lining the wall, because in 1926 a woman decided to give it the dignity and efficiency of one. Her kitchen is boldly utilitarian. It’s gunmetal green because research suggested flies disliked the color. Form follows doggedly after function on every surface and in every cubby. She created the first fitted, or built-in, kitchen. Complete with standardized cabinets and standardized liberation. 10,000 of Lihotzky’s Frankfurt Kitchens were built in New Frankfurt.

In 1930, bouyed by the success of her kitchen, she accepted a commission to help design cities for the first of Stalin’s Five-year plan. The first plan was supposed to turn the Soviet Union into a great industrial power while creating a collective culture. The industry and culture would help realize a world of Soviet of ideals. Ideal worlds often extract great human costs. People were imprisoned so they could provide the hard labor of world building. Agricultual land owned by the peasant class was collectivized through brutal, bloody force.

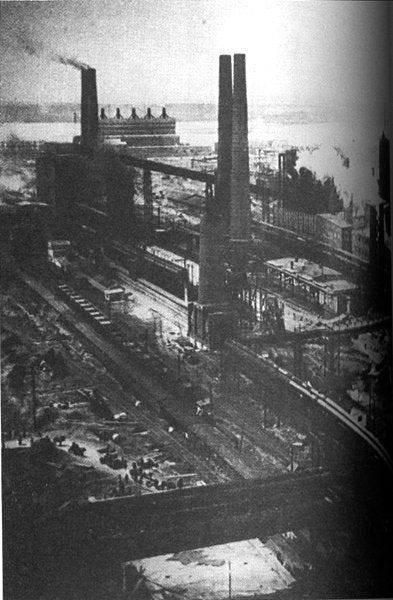

Lihotzky helped design Magnitogorsk, an industrial city built around steel production. She was joined by many others. An American consulting firm helped design the steel plant at the heart of the city. The famine caused by collectivization killed millions. Lihotzky must have been fine with the layout, people kept dying but she remained. Magnitogorsk served as a shining example of the supremacy of the Soviet Union.

Even the architects who helped build Stalin’s world were not safe.

She finally fled the Soviet Union in 1938 during Stalin’s final Great Purge. Even the architects who helped build his world were not safe. In 1940, she returned to Vienna to join the resistance against the Nazis. She was caught by the Gestapo and jailed for four years. Her liberation was designed by US troops in 1945. Despite the success of the Frankfurt Kitchen, Lihotzky was not invited to help rebuild her country after the war. People were too wary of communist design. She spent the rest of her career working as a consultant for communist governments, rationalizing liberation through standardized measures.

The iron and steel works of Magnitogorsk are still in use. People live in its shadows and smoke in homes Lihotzky helped design. It's been ranked one of the most polluted cities on the the earth. In the early 90s, the pollution was so overwhelming only 28% of babies born in the city were deemed "healthy".

The Frankfurt Kitchen sought to help women put drudgery in its place. 20th century American appliance advertisements promised to free women of the drudgery altogether. Washing machines, dryers, dishwashers, toasters, refrigerators, garbage disposals and adjustable temperature irons all made their first domestic appearances in the first half of the century. Once appliances could be mass produced, they needed to be sold. Thanks to planned obsolescence, once they were sold, they’d always be bought again.

In the 1920s and 30s, appliance advertisements called appliances “invisible servants”. By the 1950s, the domestic help angle was dropped in favor of domestic pride. Kitchen design was overtly political once again. The innovation available in every American kitchen was proof that American capitalist consumerism would defeat the Soviet Union’s communism. Every toaster served as a shining example of the supremacy of the United States.

The purpose of the home was remade. Historically, homes have been a unit of consumption and production. Some homes consumed grain while producing children and textiles, for example. In Cold War America’s propaganda and policy, the home became exclusively a unit of consumption. The kitchen was the consuming center of that home. It was a white woman’s patriotic duty to have a house full of capitalist produced, time-saving appliances. She was supposed to use her saved time to devote herself to the American model of womanhood - a careful, carefree housewife with pristine children and a pristine home. Her home wasn’t a work space, it was a lifestyle.

You could hardly pay a woman for her work in the home if you were determined to prove consumerism ended her work.

Marietta Shaginian, a Soviet journalist in the 1950s, called the American “kitchen ‘ideologically inappropriate’ because it was designed not to help the working woman achieve self-realization but to compensate the middle-class ‘professional housewife’ for her lack of a place in the public arena.” Bold words from a woman whose country was institutionalizing people for voicing anti-communist sentiment in the public arena. But she was right about the ideology behind the showroom kitchen. American house wives were not expected, or welcome, in the public arena. And they certainly weren’t about to be paid for their work in the private arena. You could hardly pay a woman for her work in the home if you were determined to prove consumerism ended her work.

The crusade for consumerism continues in America. We do not acknowledge the economic value of unpaid labor in our GDP because we still consider homes units of consumption. If American homes are really all consuming and never producing, then they should be rich proving grounds for the ideology of consumerism. But they aren’t. Mass consumption doesn’t save women from work. In a Pacific Standard article about the subtle sexism of home technology, Dr. Yolande Strengers says, “new domestic technologies entering the home (like vacuum cleaners, washing machines, and irons) have increased expectations of cleanliness, and that burden has been disproportionately felt by women because they still do most of the housework.”

Who is this designed to serve? I don’t think the answer has anything to do with the person who works in the kitchen.

I can’t shake Strengers’ words as I look at the pictures of apparently appliance-less kitchens of the rich. If the fridge must be hidden then what of the bananas on the counter, the crumbs on the table, the dish in the sink? What about the broom, the dish rag, the cutting board? Where do they go in a space that is designed to sustain the hollow forms of “pretty and seamless”? Who is this designed to serve? I don’t think the answer is has anything to do with the person who works in the kitchen. Actually, I know that is not the answer. Because I am a person who works in the kitchen. Pretty and seamless are not design elements it is pretty or seamless to maintain. I suppose the very wealthy have underpaid housekeepers to keep up the appearance of a lifestyle without work.

Some feminist architects envisioned a life truly free of domestic work spaces. They sought to free white women, and their homes, of kitchens altogether. In the early 1900s, Alice Constance Austin was commissioned to design a socialist commune of kitchenless houses. Food was to be cooked in a central kitchen and sent to communal patios by a series of underground rails. Dirty dishes sent back to the central kitchen for cleaning. Laundry would be taken care of this way too. The central kitchen staffed with paid labor. Whose labor and what kind of pay?

Applications to become a member of the commune were open exclusively to white socialists. The commune’s founder didn’t think it was “expedient to mix the races in these communities." It is difficult to imagine their employment terms would have been more enlightened than their membership terms. There's no way to know. Austin’s vision of a home without a hearth was never built. The commune fell apart over a lack of water and leadership.

Sometimes the kitchenless house got literary support. Remember reading The Yellow Wallpaper by Charlotte Perkins Gilman in high school? A feminist classic, it’s widely undersood as a tale of oppression by patriarchy and domesticity. But it's not the only thing Gilman wrote. In Women and Economics, Gilman opines:

“Take the kitchens out of the houses, and you leave rooms which are open to any form of arrangement and extension; and the occupancy of them does not mean ‘housekeeping.’ In such living, personal character and taste would flower as never before… The individual will learn to feel himself an integral part of the social structure, in close, direct, permanent connection with the needs and uses of society."

Certainly a house without a kitchen still holds people who need to eat. If the men and women of the house aren’t doing housework, who is? Who is dusting those rooms where taste flowers and the form of society itself is touched? For Gilman this was “a need for labor unmet.” In 1908, she published a paper in The American Journal of Sociology explaining how to meet that need. It titled, A Suggestion on the Negro Problem. Gilman wrote that mere fact of Black people in America caused "social injury.” Her “suggestion” for that "problem"? A forced labor corp, complete with uniforms and bases.

She argued that Black people "should be taken hold of by the state” and “enlisted” into forced labor. “Men, women, and children, all should belong” to her “proposed organization.” The “enlisted” would be made to labor on farms, in mills, and in building roads and harbors. Gilman suggested the state build “a training school for domestic service” at each enlistment base. Once trained, “individuals could be sent….on probation...to remain out in satisfactory home service. In case of unsatisfactory service they should be reenlisted.” In Gilman’s ideal world, Black people were “free” to clean Gilman’s house or face enslavement.

Racist socialists eating food prepared in centralized kitchens staffed by underpaid people is dystopic. Gilman’s vision is chilling and violent. It’s hard to consider that dystopic, chilling, violent things have much to do with our warm reality. But if reality feels warm, it's probably because you are in a room designed for your comfort. How many white women found their consuming feminism on the unpaid and underpaid labor of others?

Racist socialists eating food prepared in centralized kitchens staffed by underpaid people is dystopic. Gilman’s vision is chilling and violent.

White communists, white socialists, white feminists, white capitalists and white supremacists all hoping to engineer whole societies by designing the kitchen. Each saw kitchens as permanently fitted with women - they just disagreed over what that meant. All kept the footprint of patriarchal understanding and most anchored deep into racist foundations. None of their blueprints made room for the meaning of the work in the kitchen. Forget the meaning, they could hardly be bothered with the function. Lihotzky, with all her research into pantry placement, didn’t seem very concerned when peasants' pantries were made fatally empty. She wanted to design a world for certain women, in a certain way. If other women starved while that world was built, maybe it was because they didn’t deserve to be part of the design.

What impact can fitted rooms have if the women who live in them are consistently, deliberately, designedly disempowered?

This started out as snippy little essay about design but I can’t seem to muster the energy to finish with much zip. Is kitchen design still a political act? For good or evil? For the people the kitchen serves or the people who serve in the kitchens? I don’t know. What impact can fitted rooms have if the women who live in them are consistently, deliberately, designedly disempowered?

We claim the moral high ground. And then exploit the labor of other women to keep the high ground clean. We insist that women do not just belong in the kitchen. And then do nothing when moms are forced out of the workforce because of the pandemic. We are adamant that the work of the home is real work. And then pretend full-time unpaid caretakers do not exist when discussing economic policies. We embrace gender equality. And then men continue to not do house work. We say women should work outside the home to provide for themselves and their children. And then refuse to fund universal childcare. We say women should stay home with their children. And then refuse to pay them for the work they do in the home.

We claim the moral high ground. And then exploit the labor of other women to keep the high ground clean.

We preach that American women are free in their kitchens and outside of them. And then our highest court lets private citizens enforce an unconstitutional law with a vigilante bounty system. We force women to carry a pregnancy because it’s about time American women come to terms, I guess. And then we charge them thousands of dollars to deliver the baby and make damn sure that motherhood never stops costing them, ever. We tell mothers that we know their children are worth it. And then we let guns into their children's schools and put bullets into their children's bodies.

Is there line of cabinets deep enough to hold our grief?

Engineering worlds around kitchen design hasn't worked. Maybe it's time to design the kitchen for the world we've engineered. Women have traditionally cooked in the kitchen. But they've wept and screamed there too. What work surface will bear our scratches best? Is there line of cabinets deep enough to hold our grief? No need for a freezer. I am not even sure what there is to preserve.

And you know what? Let's do use our fitted cabinets to hide our time saving appliances. Why pretend the substance matches the surface? Hell, we could just start covering everything with cabinet panels. Visitors will walk into my house and have no idea where the kitchen is. The new status symbol is an invisible kitchen. Everything is cabinet now.

Yikes Charlotte Perkins Gilman. Yikes Yikes Yikes.

This was an outrageously good article. I'm only sorry it took me so long to discover your writing.